Parasites have a bad reputation – so much so that they are used as an insult. But is their reputation deserved?

Mike Gardner is a Professor in Biodiversity/Ecology at Flinders University. He says parasites play a key role in healthy environments.

“There are very intricate relationships between animals and their parasites,” says Mike.

“They’re an essential part of ecosystems.”

Parasites help energy flow through food chains. They keep host population sizes in check and are an indicator of healthy biodiversity levels.

sucking out secrets

Parasites can also reveal secrets about their hosts.

A recent study by UWA and the Australian Institute of Marine Science looked at parasites found on the lips of whale sharks at the Ningaloo Reef.

The scientists collected a small, parasitic copepod, Pandarus rhincodonicus, from 72 whale sharks over six years.

The copepods revealed information about the whale sharks’ diet and feeding strategies.

© AIMS | Andre Rerekura

© AIMS | Andre Rerekura

tick talk

The team used microchemistry techniques to look at nitrogen-stable isotopes within the parasites.

“These [isotopes] give us information about the animal’s position in the food web,” says Brendon Osorio, lead researcher of the project who’s based at UWA’s School of Biological Sciences.

“Low nitrogen isotopes tell us they sit low on the food web, like a herbivore. High nitrogen isotopic values tell us they sit higher on the food web, like a predator.”

They checked the copepod’s values against paired skin samples from the whale sharks.

High correlations meant the parasites could act as reliable representatives of the whale sharks’ diets.

tick-ing all the right boxes

© AIMS | Andrea Rerekura

Because whale sharks often feed in very deep water or at night, observing their feeding habits can be tricky.

“Traditionally, when we wanted to look at their diet, we’d have to get in the water with them or use chemical approaches,” says Brendon.

“Collecting their tissues, like blood or skin, can be quite difficult.”

“We used parasites for our research to find a less-invasive and easier way to collect samples that we couldn’t really beforehand.”

hosts with the most

Furthermore, parasites can give scientists an indication of an animal’s general health.

Hosts and their parasites are thought to co-evolve.

Over time, the host becomes somewhat accustomed to the parasites and can tolerate their presence.

When more parasites are present than usual, it can be a sign that something is wrong.

“If we find a large number of parasites on an animal, we expect that animal’s probably got some other issues as well,” says Mike.

unsolicited tick pics

The presence of parasites might also give the host’s potential partner an idea of their health – and fitness to mate.

Mike’s research focuses on lizard host/parasite relationships.

According to him, if male shingleback lizards have a large parasite burden, their partner is less likely to mate with them.

“These animals are monogamous. They pair up with the same mate each year,” says Mike.

“If a male has a lot of parasites, their likelihood of regaining their mate is reduced.”

“Lizards can tell there’s something going on.”

A parasite’s life for me

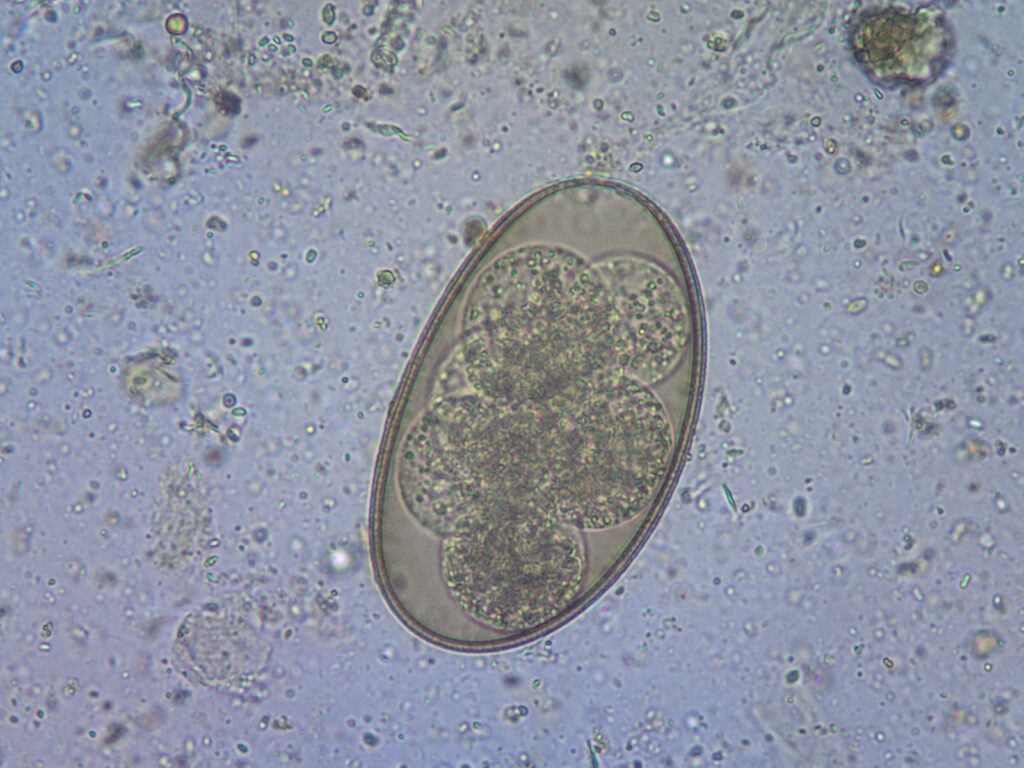

A parasite is defined as an organism that takes nutrients from another species.

But they usually need their host to stay alive so they don’t want to hurt them too much.

“It’s not in their best interest to kill everyone,” says Mike.

“They’d get themselves out of a job.”

Surprisingly, parasites can evolve over time to become less virulent and more benign.

“That might go right down the road of symbiosis, where both parties are benefiting from it,” he says.

“[For example], there are nematodes or cestodes we think are probably involved in helping digestion [in lizards].”

what makes them tick?

However, a lot of the time, we don’t know how parasites affect their hosts.

This is the case with the whale shark copepods.

“We suspect they consume their skin or … some blood, but we don’t know exactly how that impacts whale sharks,” says Brendon.

“They haven’t been studied all that much.”

Mike suggests that, in some cases, host species are worse off when their parasites are removed. This has been noticed during relocations of endangered lizard species.

“It provides a bare ground for new parasites to invade them – ones they haven’t evolved with,” he says.

hanging in the balance

The chances of encountering unfamiliar parasites could be increased by climate change.

“It’s changing the range of different species and may bring them into contact with parasites they haven’t been exposed to before,” says Mike.

“There are conservation concerns because endangered species might not cope with those new parasites in their range.”

Like any natural member of an ecosystem, when it comes to parasites, it boils down to maintaining a healthy balance.

“If we didn’t have parasites, it would be a massive problem,” says Mike.

“It’s important to have that balance in our ecosystems.”